My Time As A City Boy

Let's Start From The Beginning

I often talk about avoiding stress on this blog and mention how I’ve had stressful jobs in the past. It’s about time I addressed those jobs, most of which were as a "city boy" or "maintenance worker" for small towns. I’ve avoided even thinking about them for the better part of a decade, because they still bring me anxiety. But I want to get it out there and address it. This post will likely evolve as I recall or even re-remember things differently. Take it all with a grain of salt, because my memory is pretty rough—going back two decades makes much of this patchy at best.

Let's Mow Some Grass

My first job as a city boy was when I was around 21, probably in 2002, when a friend of a friend became mayor of my small hometown. The new mayor’s name was Mike. I won’t use full names, because I’m not out to bash anyone or drag their name through the mud. This isn’t a petty post; it’s for my own sanity, if anything.

When Mike became mayor, I half-jokingly said, "I need a job; hire me!" I did need a job but knew nothing about maintenance. Mike, a people pleaser by nature and an all-around nice guy, had been a city worker himself. He’d quit to run for mayor, thinking he could do a better job. So when he offered me a job, I was excited. Having a mayor who actually knew the work and could be a big help was encouraging.

A month after Mike took office, I still didn’t have a job. I ran into him in town and asked when I’d be getting that job. He said, “I’ll figure something out.” From the way he said it, I figured he hadn’t meant it when he first offered, so I let it go. About a month later, though, true to his word, he figured something out. I started working a few weeks later after the aldermen approved me to mow grass for the summer. It wasn’t much, but it beat the terrible factories in the area.

So I jumped on it and started mowing. I love mowing grass, so I was having a blast. The city had a couple of tractors, but I mostly got an old 1976 pickup truck that broke down more than it ran, a push mower, and a weed eater. The other two employees used the tractors—well, one did. The other was lazy and spent most of his days playing scratch-off lottery tickets.

His name was Lowell. He was a licensed water and wastewater operator and a recent hire from a neighboring town. He seemed like a great fit because he lived in our hometown and had worked there before, so he supposedly knew what needed to be done—or so we thought.

He noticed my hard work and kind of took me under his wing, showing me how to do basic tasks whenever I messed up, which was a lot. He also showed me how the sewer plant worked, which fascinated me. He referred to me as “Can’t Get Right” because I messed something up nearly every day, and I asked questions constantly. I think I got on his last nerve, but he still tried his best to answer me. My rambunctiousness probably entertained him more than anything.

EPA Comes to Town

By the end of summer, I’d proved myself as a hard worker, so the board decided to keep me on full-time—at minimum wage. A few of the local citizens had noticed my effort and said I was worth keeping. I didn’t just mow; I also made it a point to patch potholes around town and trim trees from roadways. Anything I could do to improve my hometown, I was on it.

Around October, the EPA showed up at the city’s sewage treatment facility. Lowell grabbed me, and we went to meet them. When we arrived, two EPA agents were walking around, inspecting the plant. One agent took Lowell aside to review paperwork, while the other stayed with me and started asking questions. I probably had more questions for him than he had for me—I was still learning.

I didn’t realize how serious the situation was. The EPA was not impressed. Before Lowell and I were hired, the third city worker, Paul, had been left to run the sewer plant solo after the two previous workers were fired or quit. With no experience, Paul had simply copied old DMRs (Daily Monitoring Reports) that Mike, the former operator, had completed, putting his own name on them. The EPA had found out, and they weren’t happy.

Worse yet, I learned that Lowell had been doing the same thing since he was rehired. The EPA gave the city an ultimatum: fire Lowell, the licensed operator who’d been forging documents, or face a combined $11 million in fines. We were going to be fined for each day the city had been out of compliance since Mike had left as operator. The city didn’t have much choice—they suspended Lowell for an extended period of time. I believe they eventually had a meeting and decided to just let him go. But instead of putting Paul back in charge, they decided to send me to school to learn the job. I’d already taken a few classes and was unusually interested in the work.

The mayor later told me the EPA had recommended hiring me as the lead operator because I seemed curious and eager to learn. But my naivety cost me—they made me lead operator for the same minimum wage I was already earning.

That’s how this whole story really starts. Yes, it’s just now starting. Lol

Being a Dumbass

I didn’t get better at avoiding mistakes overnight. I was still the “Can’t Get Right” guy even after Lowell was suspended, and I still had way too many questions. I’d often swing by Lowell’s house to ask him anyway, even though he was furious the city had suspended him and I’d taken his job. He answered a few questions at first, but eventually, he told me to basically fuck off.

So I tried turning to the mayor, who happened to be a licensed water/wastewater operator himself—and a damn good one. But while he was our mayor, he worked for a neighboring town doing the same job as me. You’d think he’d be all over helping a young kid with a million questions, especially since I technically worked for him. But he routinely brushed me off, telling me to ask the Missouri Department of Natural Resources (DNR) instead.

So I did, and that’s when I found out we were members of the Missouri Rural Water Association (MRWA). They set me up with some knowledgeable people, and I used the chance to learn from them. At the same time, the city had a water project underway, so I took full advantage of the engineers running around town, constantly bugging them on how to do things correctly for water and wastewater.

My relentless questioning paid off. Within my first couple of years as an operator, I learned a great deal from a variety of sources—citizens, fellow operators, state officials, engineers, and field experts. This gave me a solid grasp of what to do and what to expect.

I eventually became somewhat of an expert myself in running sewage treatment facilities. It took me three tries before I passed my wastewater operator’s license, but by that third try, I knew more than most people around me.

Whenever I asked about a pay raise, given all my extra responsibilities, I hit a wall. Mike suggested I consider moonlighting in the afternoons, saying he made more money that way than in his day job. So I started taking on personal jobs for residents, doing everything from setting up printers to plunging toilets. If I set up a water tap for a resident’s house, I’d come back after hours to run the rest of the line as their plumber. I always undercharged because I never felt like I did a professional job at any of it. Jack of all trades, master of none.

It became a bit much, though. With two babies at home, I never got a moment to myself. It wasn’t uncommon to pull into my driveway and find two or three cars waiting for me—either people needing something done after work or an alderman coming by to complain about something in town. I was an hourly worker, but neither the citizens nor the aldermen cared. Anytime, day or night, they’d come to my house or call me to complain.

Enough is Enough

Mike, the mayor, was a workaholic himself and was rarely in town, so people came to me with all their problems. This is when the stress really started setting in. After about two years, I’d finally had enough. I decided to quit and applied for a job at a new factory a few towns over. It was a bit of a drive, but it paid almost double, and my off-time would actually be mine.

When I applied, they gave me an IQ test. That was a first, lol. I must have done well because they asked if I’d mind taking a second one. They didn’t tell me my score but said I was “overqualified” for the job and offered me a position on the factory floor until they could figure out something else for me. It was promising, almost like a joke, but they were serious about wanting me in the organization somewhere.

I went home, put in my two weeks’ notice, and the aldermen freaked out. Several of them came to my house and begged me to stay. It was a firm no from me. They asked what it would take, so I threw out a list of things I figured I’d never get. I wanted a time clock and pay for all city-related work—whether I was fixing water leaks in the middle of the night or fielding complaints after hours. I also asked them to get rid of Paul, my only co-worker, who proved to be useless. He spent his time at the coffee shop or spying on me, taking notes instead of helping out. He was clearly jealous that I’d been given the operator job, so I wanted him gone. I asked for two new workers—a mechanic and an all-around worker to help with mowing and other tasks.

Each morning started at the city’s only working well house, where I’d log pump hours, check chlorine levels, and do other routine maintenance. The day after I made my demands, I showed up, and one of the aldermen, Larry, was there with a time clock. Mike showed up too and told me to go to City Hall and pick out two new employees from the applications. They even said they’d match the factory’s pay. I was impressed they took the initiative to address my concerns, so I picked out two potential hires and decided to stay.

Joke’s On Me

At the next board meeting, after I’d turned down the factory job, the board decided they couldn’t afford to match the pay and hire two people. So I got only a small raise. They did hire one of my picks, a local mechanic named Bill, but for the second position, they said they wanted to hire a “Black boy.” This was the first time I’d seen diversity hires at work, lol. But I had no objections—the guy they chose was actually a great pick, and I went to school with his kids.

However, he turned down the job when he found out I’d be his boss and took a different position. So they hired a guy named Leroy (not Black). Leroy had once been married to a very influential woman in town and had even been on the school board. But along the way, he got mixed up in some bad stuff and had a bit of a reputation.

I didn’t know any of this at the time, but Bill came running to my house while the city was holding a second meeting to hire Leroy, saying, “We don’t need him—he’s a druggy.” I said as long as he could pass a drug test, I had no issues. I was glad I didn’t raise a fuss because he turned out to be not only very intelligent and a great mechanic but also one of the funniest, loudest people I’d ever met.

That Damn Kid

The next morning at the well house, Bill, Leroy, and Paul all showed up. Paul was confused as to why these two other guys had showed up. I was confused as to why he wasn't fired yet before two new guys had been hired. They had fired him, but nobody told him until that morning, making things tense. City Hall was right across the road, so I took Paul over to talk to Mike, who finally broke the news and had me drive him home. That was an awkward trip.

After that, I went back to the well house to officially introduce myself to Bill and Leroy and set expectations for running the city right. I was thrilled to have them aboard and was hoping things would improve. Bill and Leroy had a hard time hiding their annoyance that a kid was their boss—it was pretty obvious.

Oh, and we got two brand-new trucks, which was another one of my demands for staying. We went from three trucks to two, and though Bill and Leroy always rode together, they’d often disregard the daily tasks I set. They had a hard time accepting a 22-year-old as their boss.

Eventually, they warmed up to me a bit. I’m a nice, open-minded guy, so it’s hard to hate me too much once you get to know me—I tend to wear people down, lol. Even if they started liking me a bit, I doubt they respected me much. Oh well.

Salary or Hourly

The time clock didn’t last long. I was putting in a ton of hours, and now they could see it, so they decided to compensate us with time off instead of overtime pay. But there was never any time to actually use that time off, and soon my hours ballooned to nearly 200. Once I got the guys up to speed on the daily tasks, I started trying to use the time off, but this stirred up complaints that I was taking too much time off. So the city put me on salary, which wiped out my accumulated time off completely. Fun, huh?

After about a year of this, my frustration started to boil. The guys still had no respect for me as their boss, and they just wanted to sit at the shop and play dominoes all day. Eventually, I gave in, especially during the slower winter months, and would play with them. The winter before, I’d built a BBQ grill out of a barrel and cooked for everyone on Fridays. Bill, an amazing cook, started joining in, and it soon turned into daily breakfast and dinner sessions. Eventually, we’d be at the shop eating breakfast and playing dominoes until 10 a.m., then head to the coffee shop for an hour, back to the shop to chat until noon, and then take a long lunch. Not much got done.

I admit, I had a blast, but I was often the only one doing the daily maintenance while they relaxed at the shop. They were “wait for a work order” guys, while I wanted to tackle everything and anything that could improve the town. This difference in mindset caused a lot of tension. I’d also show up at the shop late in the morning because I’d go to the wellhouse first and check on the sewer lift stations in town. They took that as me being late every day. Granted, I was often late, not being much of a morning person, but I was also at work long after they went home. In my mind, it all balanced out. Unfortunately, the pay didn’t reflect the hours I was putting in.

I Need a Vacation

After a year of this, with all the behind-the-back talk and undermining, I was stressed to the max. One day, I went to City Hall and told Mike I was ready to quit. He suggested I take a week’s vacation. I told him, “Why? I can’t afford to go anywhere.” He suggested I take the family to Branson, but I barely made enough to feed my family, much less go on a trip. Still, I took his advice and took a week off, just staying home to relax with my family.

The guys did a good job holding down the fort while I was gone; they only came by twice to ask questions. But on Friday, an old friend who first suggested I work for the city came by, grinning, and said, “I can’t believe you got fired!” I thought he was joking, but he’d just talked to Mike, who told him I’d been let go for not showing up to work. Furious, I went to City Hall and confronted Mike, who played dumb about the whole vacation conversation. So did the secretary, who’d been right there when he told me to take time off.

Seeing the ruse for what it was, I said, “Screw this place.” I wanted to quit anyway; the drama and people sitting around were no good for the city. I didn’t even fight for the job. It wasn’t worth it.

Let’s Drive Some Tractors

I’d worked for several farmers in high school, but they’d never let me drive the tractors beyond the shop. I loved tractors and was intrigued by farming, so I went to a local farmer with a large farm, hoping he’d put me to work in a tractor. Dream job, right?

The farmer’s name was Larry. When I pulled up to his shop, he was talking to an older man in a truck. I introduced myself and asked if he was hiring, hoping to hop into the planting season somewhere. He asked if I had tractor experience, and I explained my limited experience driving around shops and my daily use of small tractors as a water operator.

At that, the older man perked up and started asking me about my water operator experience. I was getting annoyed since I was focused on finding a job, not chatting about city work. Finally, Larry said, “I think we might have something for you,” and gave me an address for a meeting later that day. He didn’t explain much, but I figured I’d check it out.

Back to Water

When I showed up at the address, it was a small building attached to a laundromat. Inside, there sat the old man from the truck. Turns out, he was the president of the board for one of the largest county water districts in the area. Larry, the farmer, was also on the board, and the two had been talking about needing a good water operator when I showed up asking to drive tractors. The old man, Bob Ray, was something else—demanding, quick-tempered, firm but fair. He took no bullshit and let you know exactly what he thought. He offered me a job at nearly the same pay as the factory I’d turned down, and their system was practically brand new.

I was used to working on an 80-year-old water system, so this was impressive. They had one employee, an older man who read meters, and they contracted out the labor. But after I started, I quickly got bored because there was hardly anything for me to do. The system was in great shape. They had two well houses, a booster pump house, and three standpipes. I got so bored I used GPS to locate all the water valves in the system and logged them just to keep me busy. I wasn't accustomed to the lack of stress.

Eventually, I convinced them to buy some equipment so I could handle new construction, and they bought me a used trencher, a trailer, and a new truck. They were even building a shop three miles from my house. It felt like destiny. I thought I’d found my forever job.

When they let the meter reader go because he took a week to read meters while I could do it in three days, I took over. Bob Ray quickly took to me, though he kept a close eye at first to make sure I could back up my talk. After seeing me tap a main, set a meter, and cover it up in under 2 hours, he was sold.

One day, he called me angrily as I passed him on the highway while heading back to the shop, wanting to know where I was going. I just told him, “I’m finished.” He checked, realized I wasn’t joking, and knew then I didn’t mess around. I’ve always been the hard worker, and I'm cocky about it, lol.

Years later, while working as a welder in a shipyard, my supervisor—who was a hardass—came over after talking with my leadmen. I thought I was in trouble, but he said, “Wiseman, we were just talking, and we can’t figure you out. How the hell are you not a millionaire by now? You’re the hardest worker I’ve ever seen.” That meant a lot. I was used to working my ass off and usually only getting criticism for it.

Days at the Water District

Things were going well at the water district. It was just me out in the field and Jennifer, a girl my age, running the office. We got along well, though apparently, she was upset because she’d been promised the general manager role when Bob Ray retired. That was before I came along, so there was some friction, but overall, we were fine. We learned a lot from each other; I explained what went on in the field, and she taught me about the daily ins and outs of the office.

Eventually, they hired another field guy, Stan, who’d been dealing with similar frustrations at a neighboring city. We had a lot in common and often roamed our large coverage area. On slow days, Stan liked to find a cornfield to park his truck and nap. Our district ran along the Mississippi River, so I’d often document a family of bald eagles that nested there. They flew in every morning to hunt geese, using the rice fields as a migration stop.

Beyond setting lots of water meters and reading meters monthly, there wasn’t much to do, as the system was still in great shape. I’d get bored and sand down or paint the inside of the well houses. This went on for three years until a new mayor, Greg, took over back in my hometown. One day, he asked me to help install a new pump in a lift station, then pleaded for me to come back to the city. I explained my issues from when I worked there before, but he reassured me things had changed.

Meanwhile, Bob Ray and I had been arguing. Despite the newer system, the standpipes still needed professional cleaning every 5 years, but Bob refused, thinking they were pristine. After some heated discussions, I decided to take Greg up on his offer. I told Bob Ray I’d give him two weeks’ notice to make sure Stan was ready to handle things.

When I showed up at City Hall, the clerk had no idea what I was talking about. She said they hadn’t hired anyone. I found Greg and let him have it—I’d just quit my job to work for him, only to find out there was no position. So, I headed back to the district in low spirits and stopped at a Casey’s gas station for a drink on the way.

As I got back to my truck, the mayor of the neighboring town ran up to me. They’d been trying to hire me for a year. Today, they couldn’t have picked a better time, as I was basically jobless. I told him what the district paid me, and he offered to beat it by 50 cents an hour. I said I’d hold him to it, and then explained my situation with my hometown job falling through.

Another City Job

The mayor quickly set up a meeting with their board, and a few hours later, I was hired. I had one stipulation: when my hometown finally hired me, like they’d promised, I would be leaving. I didn’t want to surprise them later. They assured me they’d change my mind—and they nearly did. I actually enjoyed my time there.

In the middle of the following week, with three days left until my two-week notice at the district was up, I got a call. Bird feathers had been found in the water filter of a nursing home in my soon-to-be new job’s jurisdiction. Not good. I drove over immediately in the water district truck and took chlorine samples at the nursing home, expecting high demand. What I found was zero chlorine in the drinking water. Given the urgency, I believe I ended up quitting the county water district that day.

What Did I Get Myself Into?

I started testing water throughout town and found almost no chlorine anywhere. I climbed the city’s two water towers, and on the oldest one—an old “witches hat” converted years prior—the hatches were wide open. Kids had been climbing in and out, leaving footprints all over. The tank had only been filling up with about three feet of water every pump cycle, making it a makeshift swimming pool.

I shut the hatches, but the lock holes didn’t line up at all, suggesting there’d never been a lock. The tank had no fence around it and no ladder guard. It was a catastrophe waiting to happen, and of course, it happened right as I took the job. Destiny, maybe?

Time to Troubleshoot

The mayor suggested using gun locks, which actually worked fine. Task one down; now, we needed a fence around the tower. A few days later, done. But it took two months of constantly flushing fire hydrants and increasing chlorine levels to fix the system. The two wells that serviced the town were only 300 feet apart (a terrible design) on the east side of town, while the nursing home was the farthest building to the west. The residents on the east side had to deal with high chlorine levels during this time as I pushed it through the old pipes, pulling the chlorine westward until I got the entire town back to normal. It took two full months.

Meanwhile, we hired a crew to sanitize the water tower and get it back in service. I also had to figure out why the water towers weren’t filling up properly, as this was causing the wellhouse to kick on every 15 minutes—a lot for a small town. The town of about 900 people was using over 300,000 gallons of water daily, triple the expected amount for a system designed for 100 gallons per person per day. With no water meters, residents paid a flat rate, which probably encouraged the high usage.

Adding to the challenge, a 24” contact pipe outside the wellhouse wasn’t effective because the frequent pump cycles didn’t allow chlorine to fully disinfect the water, leading to complaints of chlorine smell. That’s likely why the previous city workers had turned the chlorine injection so low.

The second well was offline, and the chlorine was being injected in the wrong spot. Instead of the intended injection into the contact pipe, a corroded tap led workers to run a line from the chlorine room next door, tapping directly into the main a few feet from the well.

There was no telemetry on the water towers; instead, a pressure sensor 10 feet from the well controlled the pump cycles, which was crazy to me. The chlorine was injected before the sensor, which had corroded it. So, I replaced the sensor, moved the chlorine injection back to the detention line, and got the second well online. My memory’s fuzzy, but it might’ve just been a bad check valve or something electrical.

We fenced both tanks and disconnected an old private water tower from the city’s system. After a long haul of flushing, adjusting, and monitoring, we finally got chlorine throughout the entire system, and both water towers were filling again. The chlorine smell nearly disappeared by the time water reached the households.

The Leaks and the Fault Line

We still had a problem: the city was using too much water. Situated on the New Madrid Fault (yes, in Missouri), the area constantly experiences small tremors. The city’s old cast iron main pipes were laid directly into the clay soil, which doesn’t give when the ground shifts, resulting in a lot of leaks. I don’t know how many leaks I fixed in those first months, but it was a lot, and more kept springing up.

During all of this, I was working hard to convince city officials they needed a project to upgrade the system. I won’t even get into the city’s lagoon system, which was in just as bad of shape and grossly out of compliance.

After about six months, the city officials finally agreed that something needed to be done. They called in an engineering firm to start designing a new water system and a new sewage treatment facility.

The state officials had been watching me closely through all this, nervous that someone might get sick and they’d face a PR nightmare. I didn’t know it then, but they nominated me for Water Operator of the Year. I won!

A Surprise Award

As operators, we’re required to take continuing education classes each year. Later that year, while at a class, another operator congratulated me on winning an award. Thinking he was joking, I brushed it off, but he insisted, saying my name had been called for the Missouri Water Operator of the Year for the Southeast District. I hadn’t shown up to receive it.

I called the state later that day, and sure enough, I’d won. They brought the plaque to me a few days later and explained that I was now nominated for the state-wide Operator of the Year award. All I needed was for the city to send in a recommendation on my behalf. When I told the mayor about it, I expected congratulations. Instead, he looked disappointed and said, “So, I guess this means you want a raise now?” I told him that wasn’t the point at all.

That reaction pissed me off! Right then, I decided that as soon as my hometown called, I’d leave. Luckily, it only took a few weeks. They needed help at a lift station, so I headed over after work one day, and afterward, the mayor pleaded for me to return. I told him I’d need to hear the same from two aldermen. He rounded them up, and a day or two later, I had my answer.

Finally Back in My Hometown

This time around, Bill had been let go, and I replaced him. Bill was supposed to have been let go the last time the mayor promised me the job, but it took them a year to work up the nerve. This time, Leroy was my boss. I was actually fine with that; by now, he’d gotten his license and, honestly, was smarter than me. I make a good gopher, anyway—if you need a tool, I go-fer it.

I did have a bit of a hard time adjusting to being the number two. Leroy insisted we were equals, but I can be a bit much. Even now, in my current job where I’m at the bottom of the totem pole, I still find myself bossing around the actual bosses. It’s ridiculous, lol.

But Leroy and I got along much better this time, and I think we became pretty good friends working together. We didn’t sit and play dominoes as much, though we did miss Bill’s cooking.

The city’s system was a lot like the one I’d just left: two wells (only one of which worked), 80-year-old water mains that constantly leaked, and an old sewer plant way past its lifespan. So I started working on the board members to bring in an engineer, just as I had in the other town. But the leadership in my hometown was stubborn—more bull-headed than any place I’d ever worked, which is saying something after dealing with Bob Ray.

After the only well went down one night, they finally agreed to let me bring in the same engineering firm I’d worked with before. The firm was hesitant; they’d been burned by this city before and said it was a nightmare to work with them. But they liked me and took my word that I’d push hard to support them. They got to work on a Preliminary Engineering Report (PER) right away.

I Was Wrong

After several months of effort from Leroy and me, along with the engineering firm, we had a game plan. We’d build a new sewer plant first since that was paramount, then move on to completely rebuild the water system. We went to the voters, and they passed a bond issue to cover both projects. But the publicity from the bond issue caught the attention of a sneaky engineer from St. Louis. Our firm, being local, had skin in the game and wanted to do the right thing. This guy from St. Louis? Not so much. Somehow, he convinced the mayor to approve an unnecessarily expensive sewer plant design that would drain the entire budget, leaving no funds for the water system.

He assured the board that he’d get “free money” later to fund the water system—a blatant lie. They cut a deal behind closed doors, and before I even knew what was happening, they fired the local firm. The local guys had already designed a simple, affordable sewer lagoon and a plan for the new water system. But now, this St. Louis engineer got the green light to go ahead with a cutting-edge, oversized sewer plant design meant for much larger populations. It was complete overkill, just a way to milk our funds. Worse, he didn’t even design it himself—he was just a middleman for a large firm that did it all for him.

The city was being duped, and no matter how much I tried to explain, they wouldn’t listen. We needed both projects to be shovel-ready before the 2010 census so that we could base new rates on the 2000 census, which would keep water and sewer rates lower for residents. They wouldn’t listen. After three years of banging my head against the wall, I’d had enough.

Hanging It Up and Running a Restaurant

I’d gone in as a silent partner on a local restaurant while all this was happening. My partner eventually quit, and since I was the only one with money in the venture, I walked away from the city job one day and went full-time at the restaurant. This lasted about two years. Things were going well until they weren’t. Summer months were rough financially, but when school was in session, we made a decent living. Unfortunately, toward the end of our second or third summer, we got robbed, and it happened at our lowest financial point.

Let’s Try Welding

I didn’t sell the restaurant immediately, but I got a full-time job at a manufacturing plant building train cars. I wanted to sell, but my wife loved running the place, so I let her keep at it. It lasted another six months, lol. I worked at the plant for a few years, and it was rough. I wasn’t actually a welder at the time; I was a fitter, and it was brutal. I was good at it—I broke a few records—but it took a toll on my body. I wanted to quit, but the money was good, way better than what I’d made at the city.

One spring day, I remember the windows were open because it was so nice out. I worked nights, so this must have been in the afternoon. I was just waking up when I heard someone whispering my name through the window. Rubbing the sleep from my eyes, I got up in my boxers, walked to the window, and threw open the curtain. There was Greg, the mayor, whispering my name instead of knocking on the door like a normal person. I say that with love because I really did like Greg. He cracked me up with things like that. Greg, along with many others I’ve mentioned in this story, has since passed away. They were all really good people.

Third Time's a Charm

As I sleepily looked at Greg, he said, "We need you back!" I just laughed. "Dude, I’m making way more money than you can afford," I said. He asked how much, so I told him. Then he replied, "We’ll match it!" I was skeptical. "Yeah, okay, I’ve heard that before," I said. But a few days later, they actually offered to match my pay to bring me back. Leroy had left the city shortly after I did, thanks to the whole sewer plant ordeal, and they’d hired a couple of local guys to take over. Neither of them had any experience and no one to train them. They had a brand-new, state-of-the-art sewer plant coming online in a few weeks and no one who knew how to run it—a whole reason they should’ve gone with a simpler lagoon design in the first place.

Like a fool, I took the job again. For the third time. By then, I’d been out of the game for nearly five years and had to retake the exams to get all my water and sewer licenses. I scored over 95% on all three exams with no studying—yeah, I’m bragging, lol.

But when I officially took over, I got the news that they couldn’t actually match the pay they’d promised. So, once again, I’d taken a pay cut. Go figure.

The new sewer plant was an Aero-Mod, combining oxidation and clarification in one process. It took me some time to figure out, especially since the St. Louis engineer was long gone by then. But after a few months, I had it under control.

One of the new guys quit as soon as I took over—apparently, my reputation preceded me, so the trash took itself out, as far as I was concerned. The other guy took a while to warm up to me, but like I said earlier, I have a way of wearing people down. Eventually, we got along well. Things started off decently, but I still had an agenda: we needed that new water plant.

After several months of nagging, I finally convinced the city to work with the original engineers again. They’d already designed the water system, and it was nearly shovel-ready. But the engineering firm was gun-shy and didn’t want to get involved after spending time and money on the city before and not getting paid. I used that as leverage, telling them to ask for payment upfront for the PER. The city agreed and paid them, and we were ready to go—or so I thought.

Mr. St. Louis somehow slithered his way back in and convinced the city to drop the firm and go with him again. Even after the city had just paid for a shovel-ready project, they listened to him. I was so angry I nearly quit then and there.

With elections coming up and two aldermen positions up for grabs, I encouraged a couple of smart locals to run, then I pushed hard for them. One candidate was Greg’s brother, an extremely sharp guy, and the other was a woman I went to school with who was also very intelligent. Both won! I was excited but had a lot of work ahead. I went to Greg’s brother the day after the election, ready to bring him up to speed on the water project and give him the numbers to crunch. I thought he’d understand and help me get this going.

Nothing Comes Easy

Nope. Instead, he bulldozed his way into the first board meeting and shut down the water project completely. So, I turned to the new alderwoman, but she found me first. She didn’t want to hear about the water project; her main concern was a water leak on her property.

To get on her good side, I went to check it out and found the leak was in an empty lot next to her house. This was strange because an old house had been there, and the water meter was shut off, so there shouldn’t have been a leak. I shut off and locked the meter, thinking that would solve the problem. Nope. I got called back, and the lock was gone, with the leak back on.

She kept pushing me to dig up the area, and it became clear she wanted the backhoe on the lot so I’d have to level the yard afterward. She and her husband had torn down the house and wanted the lot leveled for free. I told her no, and that she should be fined for tampering with the lock and wasting water. But instead of doing the right thing, the mayor sent my coworker to level her yard behind my back. Even ten years later, I still think she was a jerk for that.

After the incident, she started a smear campaign to turn people against me. She got this one older lady on my case, and to this day, I have no idea what she told her, but that woman was out for blood.

You’re Welcome

When the town’s only well went down again after a lightning strike, I faced a tough situation: the lightning had fried the starter, and without it, we had no way to run the well. Luckily, I knew there was an older wellhouse in town with unused components that had never been used. I took the starter from there and got our main well running again, sparing the town from what would have been a prolonged water outage.

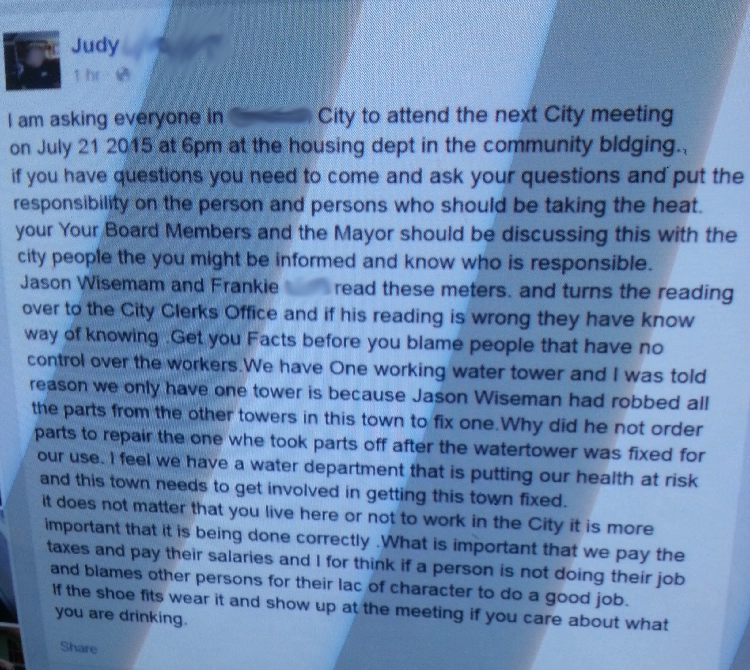

But that’s not the story that spread. An older lady in town started a rumor that I was “robbing parts” from one water tower to fix another, insisting that we only had one functional water tower left as a result. In reality, both towers were fully operational, and her claim was absurd. The two water towers were built 50 years apart, with completely different designs—making it physically impossible to swap parts between them, even if I’d tried! There’s just no way to “borrow” parts from a water tower.

I never corrected them or entertained the lunacy even though I had proof and still do. This is the part I stole from one control panel and put in another so they wouldn't run out of water.

Two brand new starters that have been sitting there for years, I used one to keep the town running. That was it. Both water towers were fine and in service the entire time.

Two brand new starters that have been sitting there for years, I used one to keep the town running. That was it. Both water towers were fine and in service the entire time.

Teachable Moments (Or So I Thought)

Each emergency presented a chance to show the board the importance of preventive measures and investments in our infrastructure. But instead of heeding my advice, they took my explanations and twisted them into something sinister. Before I knew it, I was branded as the guy who was “robbing parts from water towers.” The idea was laughable—what was I supposed to have done, stolen a whole leg off the tower?

My mistake was assuming that common sense would prevail. What I fool I was.

Enough Is Enough

At this point, I’d had it. I was beyond stressed trying to help my hometown, and all I ever got was my name dragged through the mud. Every single time. Both the first and third times I worked there, the city was out of compliance and facing massive fines, and both times I got them out of it.

The final needle that broke the camels back was when they hired a new city clerk. No matter how hard I tried she just did not like me. I couldn't figure out why for the longest time. Then one day I was having trouble at the wellhouse and she undermined me as I was talking to the mayor about the problems. She insisted we bring in another operator she knew that was more knowledgeable than me to fix the problems. I'm always up for learning so I was excited to bring in an outside prospective.

When the guy showed up, everything made sense. He was the water operator from the town that the new city clerk originally worked at. Everything made sense because I knew that guy was out of a job. I was so deflated from the talking behind my back when all I ever did was try to do what was best for the city that I didn't even fight it.

I quit for the final time shortly after when it was clear my name was being drug through the mud once again. He was hired immediately and both he and the new city clerk didn't last but a few months before their true intentions got them both in hot water. I'll leave it at that.

I’ve left more out of this story than I probably should have, and I may add more as I remember it. My time as a “city boy” was the most stressful experience of my life. Reflecting on it, I realize I loved the job itself—it was the endless misunderstandings and lack of trust that wore me down.